A Field Reminder of the Uniqueness of Plum Island

November 26, 2014 by Chris Hein

Williamsburg, VA

Two weeks ago, I had the opportunity to work with several collaborators from the University of North Carolina on a study of overwash on a barrier island in New Jersey.

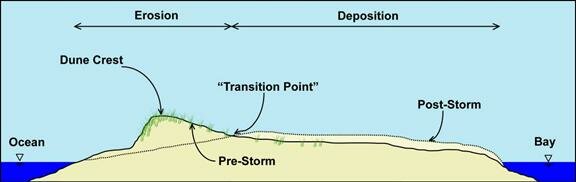

Overwash is the flow of water and sediment over the top of a barrier, generally during a storm. The result is widespread erosion of the beach and dunes, and the deposition (dumping) of that sand on the back (landward) side of the barrier island. This image, modified from the Department of Transportation (Figure 8.16 of: http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/engineering/hydraulics/pubs/07096/8.cfm), shows this process well:

We were out on the Holgate Wildlife Refuge, located at the southern end of Long Beach Island, NJ. It is a location in some ways similar to Plum Island – a piece of a developed barrier island that is kept natural because it part of a refuge, this beautiful, 3.5 mile long stretch of beach is home countless birds and birders alike. We spent three very cold days collecting ~75 sediment cores with a handheld Geoprobe system and several miles of ground-penetrating radar profiles (see earlier posts on our use of these tools on Plum Island). This was part of a study to quantify the volume of sediment overwashed during a single event – Hurricane Sandy . . . or “Tropical Storm Sandy”, which it technically was when it struck the coast . . . or “Superstorm Sandy” which is what the media preferred.

Chris Hein and Laura Rogers (a graduate student at UNC Chapel Hill) collecting a handheld Geoprobe sediment core on Long Beach Island, NJ, in November 2014.

Long Beach Island was devastated by Hurricane Sandy. Roads in the town of Beach Haven, immediately north of the refuge, were covered with as much as FOUR feet of sand by overwash. Many lost homes and businesses, and two years later, recovery continues in many ways. However, with the exception of a few gaps along the beachfront where houses were lost during the storm, most of the barrier island looks broadly similar to how it did before the storm.

Not so down in the Holgate Wildlife Refuge. Nearly the entire 3.5 miles of barrier was overwashed during the storm. Dunes were wiped out, the beach severely eroded, and literally tons of sediment was thrown onto the backside of the barrier.

This is a totally normal process on most barrier islands and it is how natural barriers maintain themselves in the face of rising sea levels. It is somewhat cannilbalistic – sand is moved from the front (ocean) side of the barrier to the back (landward) side of the barrier, eventually, over time and many storms, shifting the entire barrier landward. Barrier islands throughout the world have been doing this for thousands of years. Without human interference, most would still be doing so – just check out Long Beach Island on a map – the “natural” section of the beach located in the Refuge is sitting 500 yards landward of the developed area to the north. The Refuge section of the beach is migrating by overwashing . . . the developed section is not – in a matter of days after Sandy, bulldozers swarmed in and pushed all of that washover sand (again, 4′ covering most of the town) back onto the beach! This is certainly working in the short term, but over longer periods, the residents of Long Beach Island may have some difficult decisions to make.

An exception to this rule about natural barriers overwashing? Plum Island! No matter how bad the erosion experienced during storms on Plum Island, it does not overwash. In fact, our studies of Plum island show that it has experienced little to no overwash in the last 3000 years! The same is true for Castle Neck. Instead, on these barriers, we have HUGE dune systems (with forests . . . a little different than the picture of Long Beach Island, above). Why is this? The Merrimack River, as well as large reservoirs of sand offshore, which together provide a constant source of sediment for the beach. This is partially why we see phases of erosion and growth of the beach . . . but never wholesale migration of the barrier island.

I know this is of no consolation to those with houses in that front row on Plum Island, but working at Beach Haven was a phenomenal reminder to me of the power of the ocean and the fragility of our barrier islands . . . and how lucky we are to have a relatively stable and healthy barrier system at Plum Island.

I’ll post more on this fascinating comparison in a few months when we have more data worked up and some neat imagery to show.

Posted: February 18, 2017

Posted: February 18, 2017